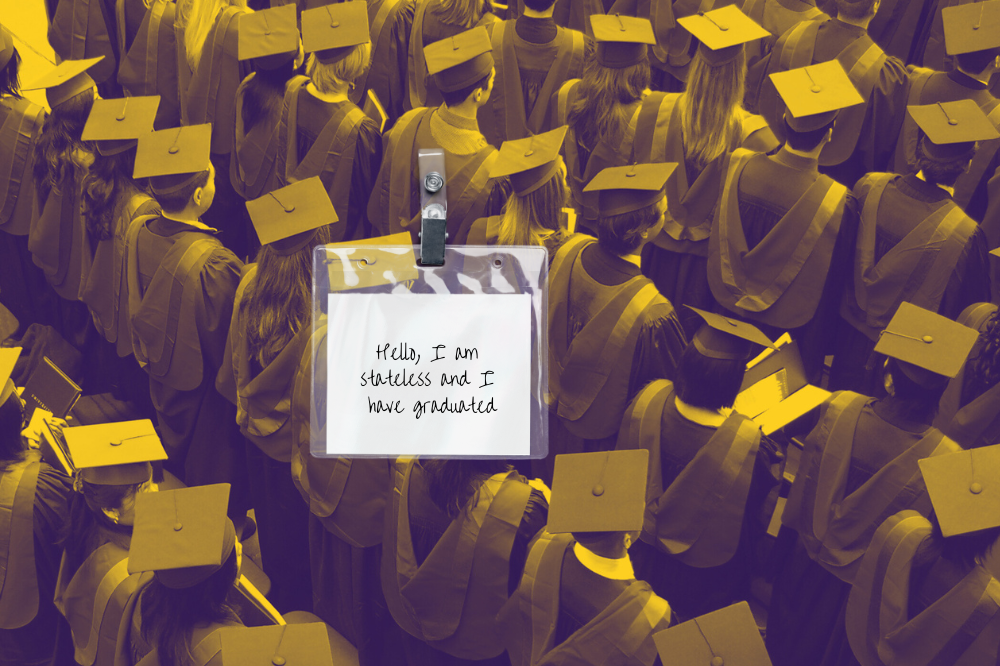

Universities must open their doors to stateless children in Malaysia

SITI NURNADILLA MOHAMAD JAMIL

IN a world where education is heralded as a fundamental right, the exclusion of stateless children from higher education remains an indefensible contradiction. These children, denied citizenship, recognition, and the basic privileges most of us take for granted, face overwhelming barriers, not just bureaucratic hurdles, but the near-impossible task of accessing an education system that was never designed to include them.

In Malaysia, this exclusion is particularly stark.

Rigid policies continue to marginalise stateless individuals, depriving them of opportunities most citizens view as ordinary rights. Universities, as institutions that champion knowledge and societal progress, must now step up. It’s time to dismantle these barriers and ensure education is accessible to all, regardless of legal status.

The Human Rights Imperative

The right to education is enshrined in international conventions, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which obligates states to guarantee education for every child, irrespective of nationality or legal status (UN General Assembly, 1989).

Yet, in Malaysia, access to education remains contingent on documentation.

Stateless children are frequently barred from public schooling and, consequently, higher education. This systemic exclusion violates international human rights standards and perpetuates the marginalisation of stateless individuals.

Stripped of their dignity and treated as outsiders, these children are denied the opportunities that could allow them to flourish.

This deliberate exclusion also exposes deeper societal anxieties about belonging and citizenship. By denying stateless children education, we are reinforcing the false notion that citizenship determines worth.

This arbitrary distinction not only prevents these children from reaching their full potential, but it perpetuates a structure that privileges some while marginalizing others.

A Personal Encounter with Resilience and Exclusion

I have had the privilege of knowing several stateless children who were determined to sit for the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM), despite facing insurmountable odds. These children lacked access to formal education, yet their resolve was nothing short of extraordinary.

While their parents’ circumstances may have played a role in their statelessness, it is the children who bear the heaviest burden.

They were left to rely on makeshift resources, volunteer teachers, YouTube tutorials, and other online platforms. I witnessed firsthand the effort it took to secure even a single day in a national school’s science lab, so they could gain the practical experience required for their exams.

These students crammed for their SPM at night, often after long days spent juggling odd jobs to support their families. Many of them, acting as sole breadwinners, carried responsibilities far beyond their years.

Yet, despite these challenges, with the support of committed educators from NGOs, they excelled. Their SPM results are not just numbers on a certificate; they are a testament to their resilience, intelligence, and sheer determination to overcome a system that has failed them.

However, even with their remarkable achievements in hand, our universities remain frozen by unfounded fears. These exceptional students, who have already demonstrated their ability to excel despite overwhelming adversity, continue to be denied access to higher education.

This paralysis is not rooted in genuine concern about capacity; it reflects a deeper unwillingness to open the doors of opportunity to those who, by every measure of merit, have earned their place.

Challenging the 'Floodgate' Fallacy

The argument that admitting stateless children would “open the floodgates” is not just misguided, it is a tactic rooted in exclusion. This rhetoric is not about capacity; it is about discomfort with expanding educational access to those historically marginalised.

The real issue is not whether universities can accommodate these children; it is whether we are willing to recognise their right to be included and their merit to be considered. The notion that stateless children pose a threat to the system is both dehumanising and misleading. It obscures the fact that these students, who have already demonstrated resilience and determination, are just as capable of excelling and contributing as any other students.

Furthermore, the bureaucratic challenges involved, such as the lack of legal documentation, prevent many from even applying to universities. These barriers mean that their inclusion would hardly strain the education system.

Yet, the continued exclusion of these students reveals a broader failure to view education as a right that transcends legal status. By refusing to welcome stateless students, universities perpetuate an outdated and unjust system that values exclusion over equity, reinforcing societal divides rather than fostering inclusion.

The Socioeconomic Ramifications

The cost of excluding stateless children from higher education extends beyond the individuals themselves, it impacts society as a whole. Education is the foundation of social mobility and economic progress.

Denying access to higher education effectively locks these children into a cycle of poverty, limiting their opportunities to contribute to society. Conversely, those excluded from education face diminished life chances and deepen social and economic disparities.

In Malaysia, stateless individuals already struggle with limited employment opportunities, often relegated to low-wage, unstable jobs in the informal sector. This not only wastes their potential but exacerbates economic inequality.

Inclusive education policies are not just a moral imperative, they are also economically sound. By integrating stateless children into the educational system, Malaysia stands to cultivate a more skilled workforce, driving economic growth and reducing disparities (World Bank, 2020).

The Role of Universities: Moral and Legal Responsibility

Universities are not merely institutions of knowledge; they are moral and societal leaders. They have a legal and ethical responsibility to promote equity and inclusion. Malaysia is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which it ratified in 1995.

This international framework mandates that every child, regardless of nationality or legal status, has the right to education. Although Malaysia has made reservations to certain provisions, such as Article 28(1)(a) on education, the country is still bound by its commitment to provide educational access to all children, including stateless ones.

Additionally, while the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is not legally binding, Malaysia recognises its significance in guiding human rights principles globally. Article 26 of the UDHR emphasizes that higher education should be accessible to all based on merit. Together, these international frameworks provide a strong moral and legal foundation for universities to adopt inclusive education policies that transcend nationality or documentation status. By adhering to these standards, universities align themselves with both Malaysia’s legal commitments and global human rights norms.

Yet, despite these legal frameworks, universities in Malaysia and elsewhere remain hesitant.

Fears of legal repercussions or institutional disruption dominate discussions about admitting stateless students. These concerns, while understandable, are largely exaggerated. Malaysian universities have the autonomy to set admission criteria, which allows them to develop pathways for stateless children through merit-based scholarships and partnerships with civil society organizations.

A Call for Decisive Action

The exclusion of stateless children from higher education is not a problem without solutions. As UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed noted, statelessness is a solvable issue (United Nations, 2019).

Universities in Malaysia must lead the way by revising their admission policies, providing targeted scholarships, and developing support systems for stateless students. It is also critical that policymakers collaborate with these institutions to foster an environment that promotes inclusivity rather than exclusion.

The time for action is now.

Stateless children are already here, striving for a future they have every right to claim. By opening their doors, universities have the power to transform lives, advance human rights, and build a more just and equitable society.

Access to education should not depend on citizenship, it is a right that belongs to all. Ensuring stateless children can pursue higher education is not only a moral obligation; it is an investment in the future of our society.

Dr Siti Nurnadilla Mohamad Jamil, Department of English Language and Literature, Abdul Hamid Abu Sulayman Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of Sinar Daily.