PMR makes a comeback? Educationist pushes for standardised examination reform

He said targets must be set to ensure that no child scores below 90 per cent of the syllabus taught.

SHARIFAH SHAHIRAH

SHAH ALAM - Lower Secondary Assessment or Penilaian Menengah Rendah (PMR) needs to be reinstated, introducing a standard-based exam system named PMR, albeit with a different approach that prioritises student progress.

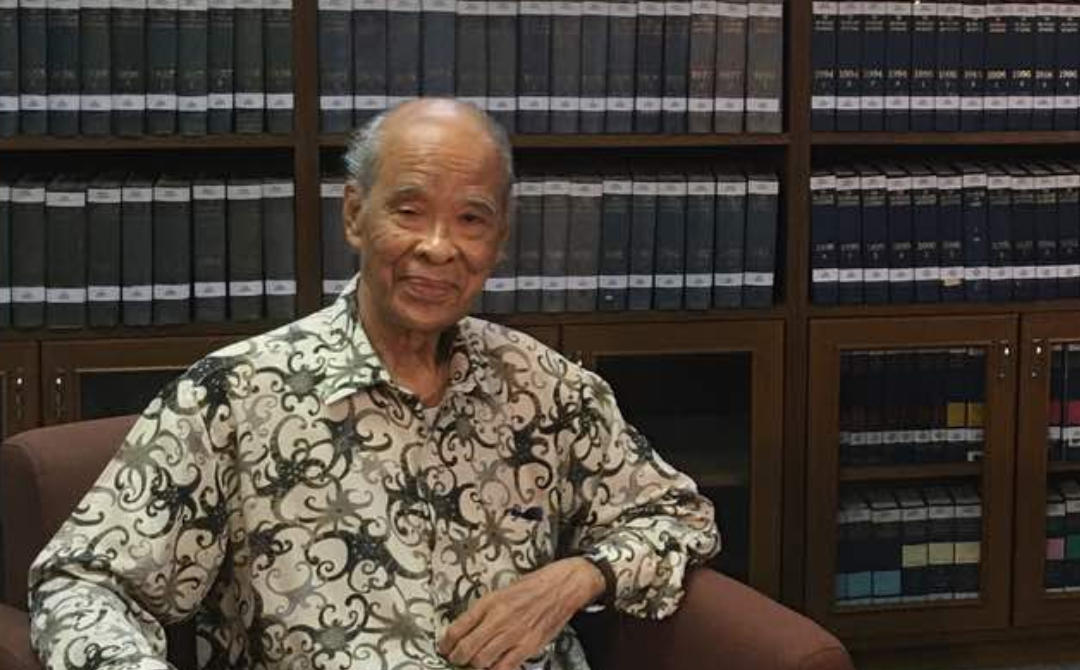

Education expert Prof Datuk Dr Ishak Haron, in this revised standardised exam, said targets must be set to ensure that no child scores below 90 per cent of the syllabus taught.

He added those who fall short of this standard should undergo isolation, remediation and receive additional instruction on weak topics.

“You may call it a standard-based exam for upper and lower secondary levels. That's what I suggest so that we can establish a target that everyone can achieve.

“However, this target is not meant to constrain us, if there's no exam, we'll have too much freedom but if the target is set high, with a very narrow scope, it will narrow down the learning process,” he said.

He further emphasised that the exam should not serve as a selection tool and was not a typical test.

Therefore, it should be administered over the years, allowing students to gauge their standards and levels.

Ishak stressed that if students were already struggling in subjects like science and mathematics, intervening during Form 3 for just five months would not suffice for full recovery as a longer-term approach spanning two to three years, starting from Form 1, was necessary to see significant progress.

He referenced the past PMR system, where students faced exam questions based on three years of learning, motivating students from Form 1 to Form 3 to prepare comprehensively.

Without exams, he said many students lack focus and targets in our educational culture, hence the importance of setting targets and not solely adopting Western learning approaches.

"If students have specific learning goals, teachers will also be more focused and goal-oriented.

“However, the methods used to achieve these goals may vary, making learning more enjoyable and meaningful.

“Without clear targets, students' motivation could suffer. Moreover, teachers lack strong Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to gauge students' progress in understanding the learning material,” he added.

Ishak stressed the importance of making every learning process engaging and interesting, spanning subjects from science to literature, English, Arabic and even prayer.

He added understanding the basics was crucial, for instance, if a student struggled with percentages, they would not grasp related math problems.

He recommended teaching percentages using real-life examples, like investments, to broaden students' understanding and problem-solving skills. Ishak said questions should be framed in a mathematical format that relates to real-world situations, enabling students to apply concepts to current events.

He said that modules could be flexible, allowing students to explore topics like food in units of varying lengths, such as one, two, or three.

The approach was to keep learning engaging and relevant to the student, fostering greater interest in subsequent lessons.

“Modular learning breaks down into 30-minute segments, focusing on specific topics within each module. This allows students to absorb information in manageable units, tailored to their needs.

“Unlike textbooks, which offer standardised content, modular learning offers a more detailed and personalised approach. Each 30-minute module caters to individual learning styles and preferences,” Ishak said.

He urged the education minister to adopt a flexible, modular curriculum for teaching and learning.

Ishak said this approach would tailor education to suit the material and adapt the teaching method to meet students' needs, guiding them step by step to enhance their learning and understanding.

Recently, the report "Bending Bamboo Shoots: Strengthening Foundation Skills" by World Bank report reveals that Malaysian students by age 15, Malaysian students lag behind peers from Hong Kong, China, Japan and Singapore in reading, science, and mathematics.

Furthermore, 42 per cent of Malaysian students failed to achieve reading proficiency by age 11, with lower-income families facing a more significant challenge, where 61 per cent lack reading proficiency.

In the meantime, 24 per cent of Malaysian children starting primary school at age seven lack school-readiness skills due to a lack of preschool education, with 10 per cent of children aged four to six not having access to preschool.

The report recommended expanding access to quality preschool education, implementing standardised learning assessments and providing ongoing teacher professional development based on international best practices.

The World Bank suggested enhancing Malaysia's early childhood learning programme while recognising the country's progress in expanding preschool education.