The enduring charm of Baju Kurung - Origins, tradition history

WHEN was the last time you donned a Baju Kurung? Perhaps during a wedding or Hari Raya celebrations, it is rarely the choice for the young ones nowadays, but however retains its classic and elegant allure.

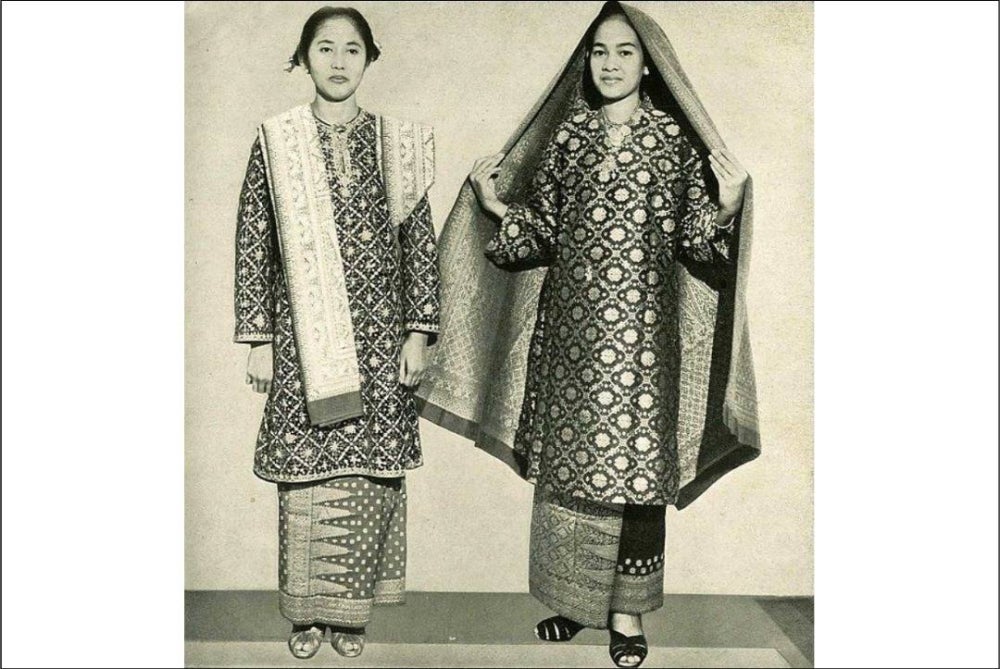

Like many traditional clothing, the baju kurung has evolved over the years, while the basic design remains generally unchanged from its early days, the modern baju kurung now features lively colours and geometric patterns and is still worn as a symbol of Malay cultural heritage and tradition.

Among the many Malay clothing styles, the baju kurung is considered by leading historians as one of the oldest and most widely adopted. Baju kurung patterns that are closely related to our local versions can be easily found throughout the region like Bentan, Bengkulu, Jambi, Riau, Padang, Acheh and Palembang in Indonesia as well as in Thailand and Singapore.

The Baju Kurung in Malaysia was said to have made its early appearance some six centuries ago during the golden age of the Melaka Sultanate.

According to the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), Sultan Mansur Shah the sixth Melaka ruler had forbade Malay women from wearing the 'kain kemban' ( a piece of rectangular cloth tied around the body, but exposing bits of the shoulder, décolletage and legs) as it was against Islamic teachings on modesty.

Following the royal decree, further guidelines were formed and gradually incorporated in the way Malay women dressed themselves in public. Even at that time modesty from the Malay perspective was largely considered synonymous with Islamic teachings that forbade any flaunting of intimate body parts, especially when a woman was away from the safe confines of her home.

A few years later, Temenggung Hassan who lived during the reign of Sultan Mahmud Shah had a bout of creativity on the existing style. He expanded the size of the Malay dress bodice to give it a loose-fitting shape, lengthened the sleeves to wrist level. It was said that he drew inspiration from the robes worn by Arab merchants in Melaka.

It was said that the term baju kurung was coined for the design because it successfully hid most areas of the female body from public view, leaving only the face and hands visible. The style then remained virtually intact for the following three and a half centuries until it was revived in the late nineteenth century and popularised once more by Sultan Abu Bakar, the father of modern Johor.

The monarch was said to have considered two main factors when revamping the baju kurung to differentiate it from the rest of the Malay garments and to make it special for the people in his state - conforming to religious rules and making the style as aesthetically pleasing as possible.

As a result, the baju kurung Teluk Belanga was introduced and became extremely popular. Aside from providing an appealing appearance, the Johor baju kurung variant is so stylish that it's no surprise that this clothing type has managed to endear itself to women to this day.

At the turn of the 20th century, the blouse length was measured as sejengkal (forefinger tip to the tip of thumb) from the ground. The length slowly shortened to mid-calf level and stayed just below the knee until the early 1940s.

At the end of the Second World War and the return of the British, exposure to foreign influences through the mass media, especially movies and fashion magazines gave Malay women ideas on ways to simplify their dressing to suit their new surroundings and lifestyle.

As a result, the baju kurung was shortened to just below the knee, and by the 1950s, ladies were confident enough to lift them above the knee by more than an inch for the first time in contemporary history.

Fast forward to Malaya's independence in August 1957, Malay women were now in the workforce, salaries earned gave them the freedom to make choices which their mothers and grandmothers could only dream about.

Instead of making their own like in the past, many began to approach professional tailors to enjoy better fitting clothes. The measurements taken were systematic and more accurate and this gave rise to new designs and cuts for the baju kurung.

By the 1960s, trendy European fabrics like as French lace and Swiss voile began to appear in Malaya. They quickly became client favourites, along with synthetic materials from China and Japan.

Seamstresses embraced these shifts in taste with gusto, as new advancements like sewing machines permitted them to try out novel stitching techniques that were cost-effective in the sense that they could do their work faster.

The emergence of western pop culture in the 1970s was the next phenomenon to have an unavoidable impact on Malay clothing in general. This was the start of the destruction and dilution of traditional baju kurung styles.

More ladies desired bodices tailored to their body curve in order to appear shapelier and more beautiful. Another request had the garment length cut so drastically that the finished result was dubbed the 'mini kurung'.

By the early 1980s, the baju kurung moden which closely matched western fashion and details had emerged. Orders to seamstresses began flooding in for baju kurung with wide shoulder construction that were heavily padded, sweetheart-shaped necklines and high ruffled collars.

In the 90's the traditional look and classic feel of the Baju Kurung was revived, with the length of the blouse restored back to knee level.

While some praised the restoration to traditional values, others, particularly the young, began to avoid wearing the baju kurung on a daily basis.It became a garment reserved only for the festive seasons and weddings as younger people preferred to dress according to their own self expression.

However the humble and classic Baju Kurung has stood the test of time, its enduring charm throughout its various evolutions, a testament to the changes in the identity of Malay women as they joined the workforce and became self-reliant.